“How can geese and flies work together to fight infections?” Well, the answer is actually simple – each can give us answers to important questions regarding which bacteria is present in a small community of geese and fly friends.

Think about it – more than ever before, humans are living in close proximity to wildlife. This is so important that the fields of Public Health, Conservation Medicine and Environmental Health came together to form the ‘One Health’ concept, which studies interactions between the environment such as the physical space occupied by wildlife and sometimes pets, and also how that space contributes to the health of all those that occupy that space, which includes humans!

One way of studying how those interactions occur is to look at the microbiome of wildlife living in natural city parks. Specifically, the gut microbiome that consists of the thousands of bacteria that are part of the natural digestive system of most animals. Science has shown that the gut microbiome is so important that it actually communicates with the immune system and can help defend against infections. This is rather different from the typical reputation of bacteria – that all bacteria are bad bugs!

In fact, when we have a healthy and strong population of ‘good’ bacteria in our gut, there isn’t much more space for ‘bad’ bacteria to invade and take over.

However, some of the bad bacteria can gain traction and develop resistance to antibiotics, and worse, that resistance can be passed to other bacteria in the gut of other animals. So, in theory, studying whether there are infectious bad bacteria or antibiotic-resistant bacteria in a fly, can actually tell us if there are reasons to be concerned about wildlife and humans.

While collecting samples from humans or pets can be quite simple, the same isn’t true for other species, like wild free-range baboons. In fact, flies have been used as an indirect way to collect and extract baboon microbiome to search for specific infectious bacteria present in the population of baboons, and researchers actually found that the flies can provide a good sentinel system to detect an infectious agent.

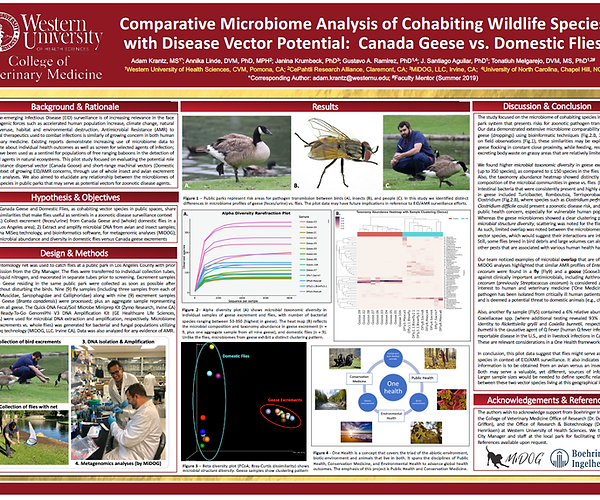

In this case of studying geese, scientists from Western University in collaboration with MiDog, LLC. performed few collections in a small scale just to determine if it was feasible to use flies to monitor the microbiome of geese that inhabit a local city park. Flies are used because they are easy to collect and can be very convenient surveillance agents for bacteria that cause diseases or that show antibiotic resistance.

With that goal in mind, scientists packed up some sample collection materials and with authorization from a City Manager in hand, headed out to a public park in the Los Angeles area. They caught some flies and also collected some geese excrements to quickly analyze the bacteria present in flies and in geese in the lab.

First, researchers compared the microbiome of all nine collected geese droppings and realized that they were very similar. Since this was a small pilot study and it only analyzed a small population of geese that flocks together in a relatively small area, these findings were not surprising.

Next, they observed that there are over 350 species of bacteria in geese, whereas only 150 or fewer species in flies. However, in geese, the bacteria present comes from the same taxon, making them sort of ‘cousins.’ In flies, however, the species present are from taxon that are not related to each other.

Now, what was really interesting to observe in the results, is that even though only a small number of samples were collected for flies and geese, the MiDog microbial testing platform was able to detect that one pair of goose + fly had the same antimicrobial resistance profile for a bacteria called Enterococcus cecorum. This particular species of bacteria has been previously linked to cases of sepsis in humans and also has been determined as a threat to domestic animals such as chicken and others.

Similarly, another interesting find was that one fly showed the presence of a bacteria species closely related to C. burnetti which is known to be linked to Q Fever – commonly reported in California livestock.

Studies like this one, even when done in small scale, are very important to determine the interactions between the microbiome of species living in close proximity to one another. Besides the obvious reasons for public health concerns, keeping healthy and happy wildlife in our natural parks ultimately improves the quality of life for all those that visit the parks, walk their pets, or enjoy a bit of nature in the heart of a city.

Categories: Antibiotic Resistance, Birds/Parrots, Gut Microbiome, Insects